Controversial_Ideas , 5(2), 5; doi:10.63466/jci05020005

Article

Silencing Science at MIT: MIT Shows that Cancel Culture Causes Self-Censorship at STEM Universities

MIT Free Speech Alliance, USA; president@mitfreespeech.org

How to Cite: Stargardt, W. Silencing Science at MIT: MIT Shows that Cancel Culture Causes Self-Censorship at STEM Universities. Controversial Ideas 2025, 5(Special issue on Censorship in the Sciences), 5; doi:10.63466/jci05020005.

Received: 28 February 2025 / Accepted: 3 October 2025 / Published: 27 November 2025

Abstract

:Polling data from the leading science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) university in the US shows that a significant degree of self-censorship is practiced by the faculty. This self-censorship stems from a fear of retaliation for expressing heterodox viewpoints, with senior administration, academic leadership, and students being the most cited sources of potential retaliation. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)’s experience suggests that similar self-censorship is likely practiced within STEM disciplines in other universities. MIT’s example also shows that the STEM faculty can respond by uniting to protect freedom of expression and academic freedom on campus.

Keywords:

cancel culture; censorship; free expression; academic freedom; MIT1. MIT as a STEM Model

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is one of the world’s leading universities overall, and the leading university in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields specifically. For the fourteenth consecutive year, MIT was ranked the world’s top university in the QS World University Rankings for 2025–2026 (Quacquarelli Symonds, 2025). MIT was also ranked first globally in 11 subject areas by the same organization, all of which are STEM disciplines. In the Times Higher Education 2025 World University Ranking, MIT placed second among universities worldwide (Times Higher Education, 2025). Additionally, US News and World Report ranked MIT’s graduate engineering program first in its latest rankings, a position MIT has held for 35 consecutive years (U.S. News & World Report, 2025a). That publication also currently ranks MIT #2 for undergraduate education among all US universities (U.S. News & World Report, 2025b).

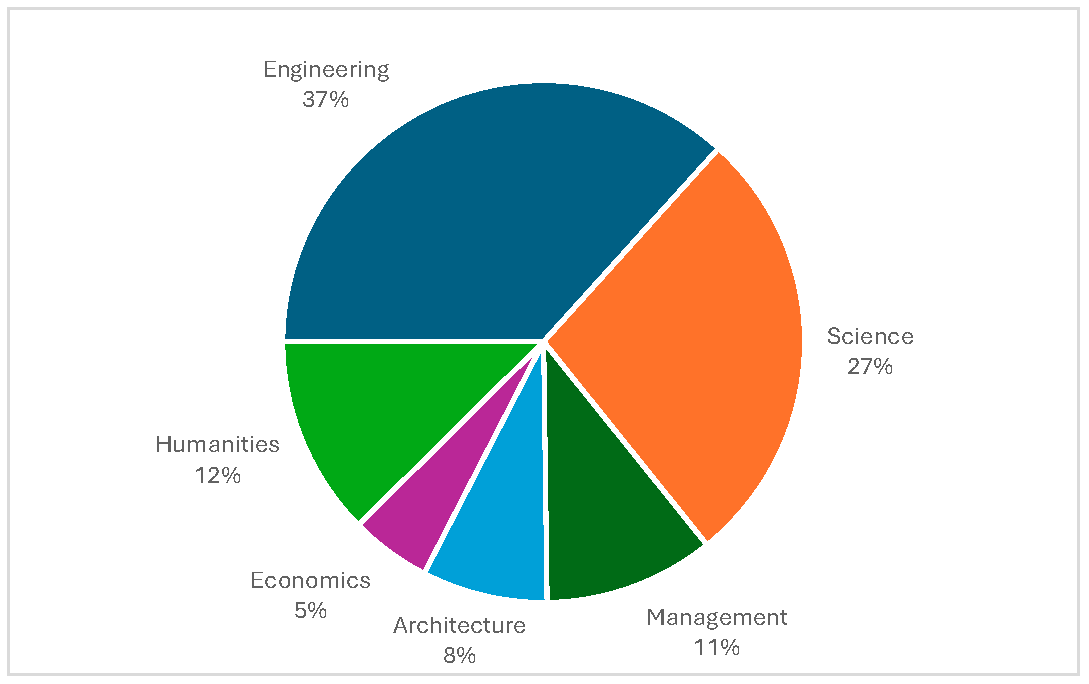

MIT is the quintessential STEM university and arguably the best of its type in the country. As shown in Figure 1, 64% of MIT’s faculty teach in the Schools of Engineering and Science, and an additional 24% teach in the closely aligned numerate disciplines of economics, management and architecture (MIT, 2025a).

Figure 1.

MIT Faculty by discipline (n = 1,079).

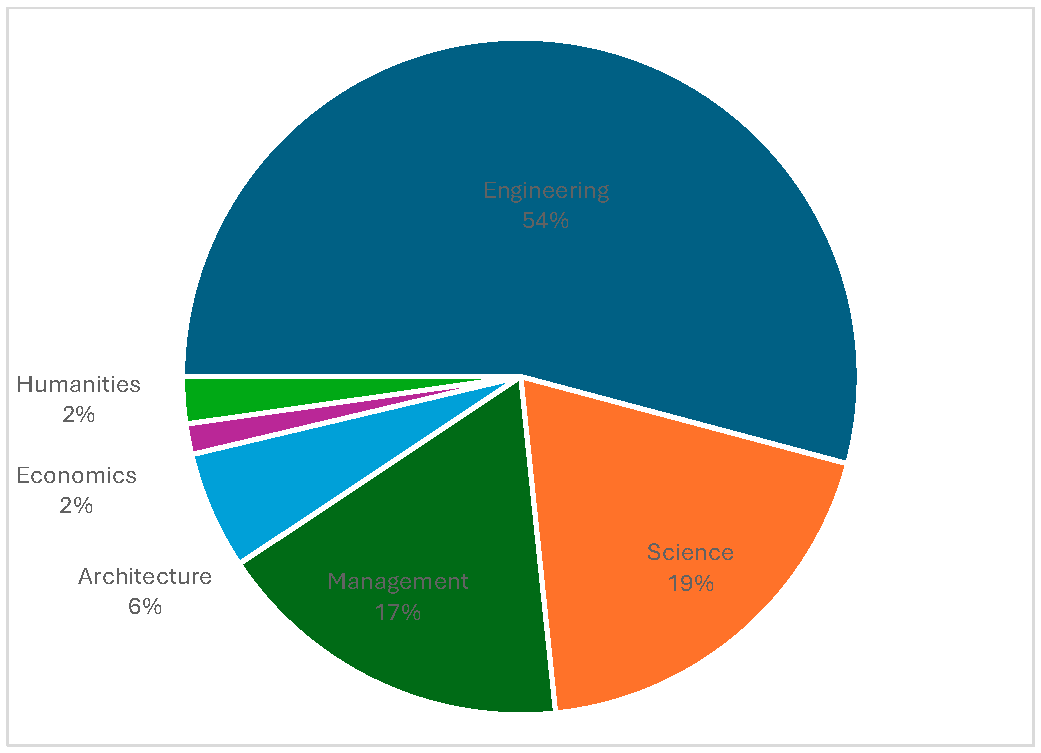

Figure 2 shows that MIT’s graduate and undergraduate students are similarly distributed, with 73% majoring in Engineering or Science, with another 25% majoring in the closely aligned numerate disciplines which also require students to complete the STEM core science and math requirements (MIT, 2025b). The overall culture on the MIT campus revolves around STEM scholarship.

Figure 2.

MIT students, undergraduate & graduate (n = 10,655).

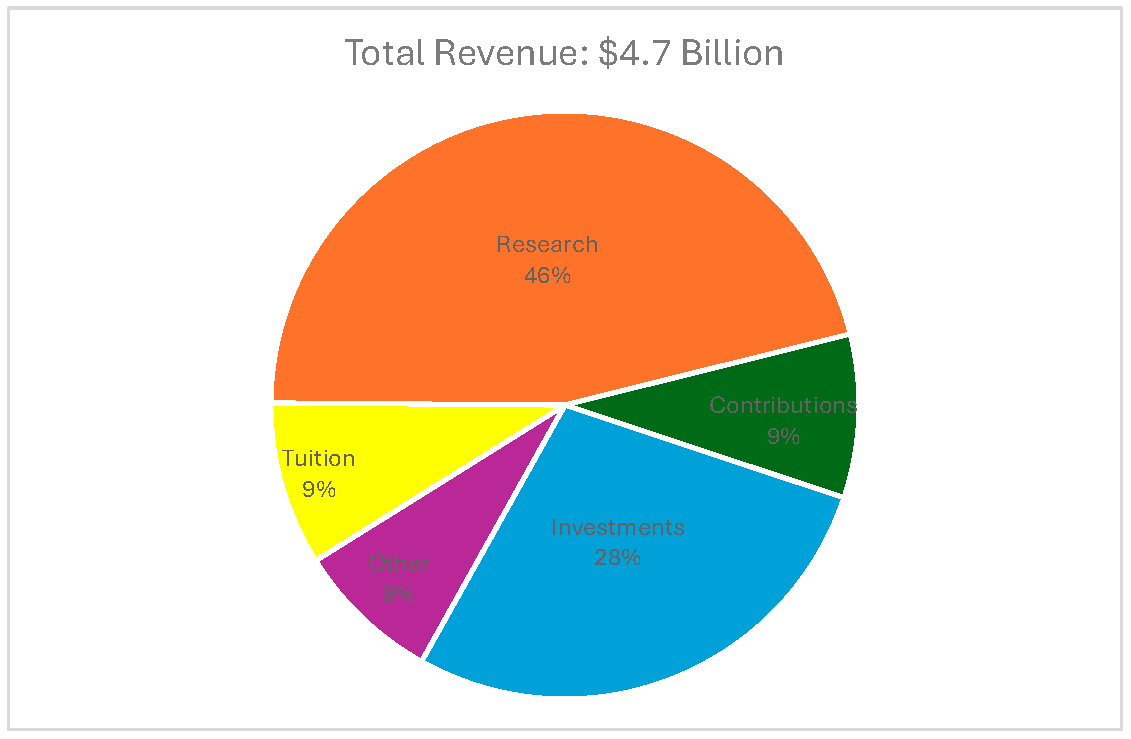

These core STEM and STEM-related fields are also keys to MIT’s financial model, in which 46% of annual operating revenues are earned through sponsored research, as shown in Figure 3 (MIT, 2023a).

Figure 3.

MIT sources of revenue.

MIT’s reputation and visibility makes it the nation’s premier STEM institution. The university serves as a shining example and source of inspiration for its peers in STEM research, education, and scholarship. What happens at MIT often sets precedents and shapes the tone for other institutions. For example, MIT was the first elite college to resume requiring the SAT (a standardized test) in undergraduate admissions following its suspension during the pandemic. In the spring of 2024, MIT became the first elite university to eliminate mandatory diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) statements for faculty candidates – a decision that made national headlines and was quickly followed by other institutions.

In this context, MIT is a bellwether for the state of free expression and academic freedom in STEM university programs nationwide. If self-censorship is a problem among STEM faculty at MIT, then the issue likely exists in STEM departments at other universities as well. Conversely, if MIT can successfully foster a culture that encourages open discourse and viewpoint diversity, its achievements can serve as a model for other universities to emulate.

MIT’s STEM-focused mission defines the composition and culture of its academic community, who are generally rigorous and numerate empiricists and who advance knowledge using the scientific method.

At most universities, faculty who are subjected to cancel culture face academic and social ostracism at a minimum. They may also lose opportunities to earn tenure or promotion. In extreme cases, cancelled faculty can lose their tenure and their jobs (Frey & Stevens, 2023).

For STEM faculty whose livelihoods depend on sponsored research, cancellation can be more severe and insidious. A major fear of STEM faculty is being secretly “blackballed” by their university from receiving research funding from outside sources. Cancelled STEM faculty can also lose access to lab space or other research resources, or to graduate students and post-docs to staff their research teams. Even tenured faculty are vulnerable to retaliation of this type, which can end a research career.

At MIT, there have only been a few overt incidents of cancel culture. In the 2000s, Prof. Richard Lindzen was ostracized at the Institute because he questioned some of the favored climate science orthodoxy (Hinkel, 2017). In 2020, in the wake of the killing of George Floyd, the MIT chaplain, Father Thomas Moloney, was forced to resign because he suggested that the community not rush to judgment over the incident (MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022a). A year later, Prof. Dorian Abbot’s presentation at the annual MIT Carlson Lecture was famously cancelled because he had separately advocated against using DEI considerations in faculty hiring and promotion (MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022b). In these cases, the MIT administration and academic leadership either abetted or allowed these cancellations to occur.

While there have not been many overt cancellation incidents at MIT itself, faculty at other universities have been cancelled with increasing frequency for expressing the “wrong” opinions on political, social, or even scientific issues. For STEM faculty, the growing politicization of science – over climate, vaccines, energy, sustainability, public health, and other issues – has added an extra threat. The MIT faculty has observed the cancellation experiences of their colleagues at other institutions. Because the MIT administration and academic leadership gave little sign that they understood the importance of academic freedom and would defend it against attacks such as the Abbot Cancellation, the MIT faculty predictably turned to an alternative defense mechanism – self-censorship.

2. Faculty Fear and Self-Censorship at MIT

Self-censorship causes hidden damage to the advancement of scientific knowledge. It suppresses collaboration, the exchange of heterodox perspectives, and the novel ideas that feed scientific progress. Both breakthroughs and incremental advances are diminished. Over time, the overall institution might suffer if faculty and students migrate to universities with better cultures.

MIT faculty polls over the four years since Prof. Abbot’s cancellation consistently show that the faculty recognizes the threat from cancel culture and are practicing self-censorship. Three different polls provide consistent indications of this practice with differing details.

Following the Abbot Cancellation, and the vociferous criticism of MIT’s actions, both internally and externally, the MIT academic leadership conducted two “town hall” meetings with MIT faculty in late November and early December 2021. These meetings were intended to deflect faculty criticism with a gaslighting narrative for the cancellation in place of the truth – that Prof. Abbot had been cancelled for his ideology about DEI (MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022c). The MIT faculty were not fooled, however, and the day after the second town hall, 15% of the faculty issued an open letter to MIT urging it to “improve its written commitment to academic freedom and free expression by officially adopting the Chicago Principles”1 (MIT Faculty, 2021).

As part of these 2021 faculty meetings, the academic leadership polled the faculty on their concern about cancel culture at MIT. About 160 faculty members participated in the meetings and the polls. This represented about 15% of the faculty, which is significant participation by MIT standards. Two questions were asked:

- “Do you feel on an everyday basis that your voice, or the voices of your colleagues, are constrained?” 56% of the participants responded “Yes” to this question.

- “Are you worried that your voice or your colleagues’ voices are increasingly in jeopardy?” 78% of the participants responded “Yes” to this question.

This first poll of its kind at MIT indicated that the faculty were both engaged in some degree of self-censorship and that they were concerned about retaliation for expressing viewpoints.

Roughly a year later, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) conducted a comprehensive Institutional Health Study on support for free speech at MIT (Frey et al., 2023). This was FIRE’s first focused investigation of the free speech environment at a single university. The study was wide-ranging, including deeper investigations of MIT’s institutions, policies, and practices, and broader surveys of student attitudes than are normally conducted for FIRE’s annual college free speech rankings. As part of this study, for the first time FIRE included a survey of MIT’s faculty.

The FIRE study surveyed 195 members of the MIT faculty (19%).2 The survey asked questions about the faculty’s views on the Abbot Cancellation, on DEI training and mandatory diversity statements for hiring and promotion. The survey also included questions about freedom of expression and academic freedom. Questions and responses around these topics included the following:3

- “How clear is it to you that your college administration protects free speech on campus?” 65% were not clear that the administration protects free speech on campus.

| Extremely unclear | 22% |

| Somewhat unclear | 19% |

| Neither clear nor unclear | 24% |

| Very clear | 16% |

| Extremely clear | 11% |

- “If a controversy over offensive speech were to occur on your campus, how likely is it that the administration would defend the speaker’s right to express their views?” 66% were not clear that the administration would defend speakers.

| Extremely unclear | 14% |

| Somewhat unclear | 24% |

| Neither clear nor unclear | 28% |

| Very clear | 10% |

| Extremely clear | 4% |

- “Compared to before the start of 2020, are you more or less likely today to self-censor on campus?” 40% were likely to self-censor more.

| Much less likely | 2% |

| Less likely | 3% |

| About the same | 45% |

| More likely | 24% |

| Much more likely | 16% |

- “How likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in meetings with administrators?” 52% were at least somewhat likely to self-censor in meetings with administrators.

| Not at all likely | 16% |

| Not very likely | 22% |

| Somewhat likely | 26% |

| Very likely | 12% |

| Extremely likely | 14% |

- “How likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in departmental meetings with other faculty?” 49% were at least somewhat likely to self-censor in departmental meetings.

| Not at all likely | 17% |

| Not very likely | 25% |

| Somewhat likely | 25% |

| Very likely | 12% |

| Extremely likely | 12% |

- “Do you feel you cannot not express your views “a couple times a week” or “nearly every day” because of how _____ would respond?”

| College administration | 18% |

| Faculty | 19% |

| Students | 21% |

The evidence of these survey responses in 2022 show that a significant portion of the faculty continued practicing frequent self-censorship. This is probably linked to the belief that MIT’s administration would not defend faculty academic freedom and the faculty’s ability to express their viewpoints freely, based on the MIT administration’s participation in the cancellations of the MIT chaplain in 2020 and the visiting University of Chicago professor in 2021. This level of self-censorship is a marked departure from MIT’s historic culture of open discourse and tolerance for diverse viewpoints.

Following its MIT-focused faculty survey in 2022, FIRE conducted its inaugural general survey of “faculty attitudes and experiences concerning free expression and academic freedom” in 2024 (Honeycutt, 2024). This survey of 55 colleges and universities included only one STEM-focused university, Virginia Tech University. Some of the survey questions originally used in the 2022 MIT survey, however, were replicated in the broader 2024 survey, although word choices for responses differed. Comparing the results of the MIT survey with the general faculty survey on the same questions indicates that the MIT faculty reflects the same overall levels of concern as faculty at other universities. STEM faculty perceive the same need to self-censor as faculty generally.

- “How clear is it to you that your college administration protects free speech on campus?” 41% of MIT faculty were not clear on administration support compared to 36% generally.

| MIT 2022 | General 2024 | |

| Extremely unclear/Not at all clear | 22% | 13% |

| Somewhat unclear/Not very clear | 19% | 23% |

| Neither clear nor unclear/Somewhat clear | 24% | 35% |

| Very clear | 16% | 22% |

| Extremely clear | 11% | 7% |

- “If a controversy over offensive speech were to occur on your campus, how likely is it that the administration would defend the speaker’s right to express their views?” 38% of MIT faculty were not clear their administration would defend controversial expressions compared to 27% in the general faculty survey.

| MIT 2022 | General 2024 | |

| Extremely unclear/Not at all likely | 14% | 7% |

| Somewhat unclear/Not very likely | 24% | 20% |

| Neither clear nor unclear/Somewhat likely | 28% | 41% |

| Very clear/Very likely | 10% | 25% |

| Extremely clear/Extremely likely | 4% | 7% |

- “How likely, if at all, are you to self-censor in meetings with administrators?” 26% of MIT faculty were likely to self-censor in meetings with administrators compared to 27% of faculty generally.

| MIT 2022 | General 2024 | |

| Not at all likely/Never | 16% | 15% |

| Not very likely/Rarely | 22% | 32% |

| Somewhat likely/Occasionally | 26% | 26% |

| Very likely/Fairly often | 12% | 15% |

| Extremely likely/Very often | 14% | 12% |

At the beginning of 2024, the MIT faculty independently developed their own polling among themselves. Called “The Pulse of the Faculty,” this system presents a weekly online poll on a single question. The poll is only open to faculty and is anonymous. Participation in any poll is entirely voluntary – and therefore self-selecting. Any faculty member can submit a poll question (including responses), and the faculty continuously upvote and downvote these potential poll questions. Each week the top ranked proposed question becomes that week’s poll question.

One week in April 2024, the Pulse of the Faculty ran a poll question probing faculty concerns about expressing their viewpoints. 320 members of the MIT faculty responded to this poll.4 At a 29% participation rate of all faculty, this poll had the highest participation rate in the history of the Pulse, then or since. The poll question and responses were:

- “Are you concerned about retaliation from any of the people listed below when you speak your mind?”

| Yes, from the senior administration | 27% |

| Yes, from the Deans | 27% |

| Yes, from my department head | 16% |

| Yes, from my senior colleagues | 23% |

| Yes, from my junior colleagues | 6% |

| Yes, from students or other mentees | 37% |

| Yes, from people not on this list | 15% |

| No, in general I am not concerned | 32% |

| Abstain | 3% |

These poll results indicate that a significant portion of the faculty are still concerned about retaliation from within MIT for freely expressing their viewpoints, with 65% concerned about retaliation from any source. Aside from retaliation by students, the faculty are most concerned about retaliation from the administration and academic leadership.

3. Implications

Polling data on MIT faculty over four years consistently indicates that a significant portion of the faculty explicitly engage in self-censorship. The polling data also suggests that the faculty impose this self-censorship on themselves because they fear the cancel culture retaliation that could result from freely expressing their viewpoints. Faculty are particularly concerned about retaliation from students. The next most mentioned source of faculty concern is retaliation by the senior MIT administration and the academic deans.

On the other hand, fear of cancellation by other faculty members does not appear to be the major cause for self-censorship at MIT. Some of the presentations at the Censorship in the Sciences Conference noted that one of the primary drivers of the censorship of individual faculty members comes from other faculty members. According to this explanation, faculty are the leaders in ostracizing fellow faculty members, or advocating more significant consequences, for expressing thoughts or viewpoints deemed “unacceptable.” This does not appear to be the case among the STEM and numerate-discipline faculty at MIT. This may be because the common issues over which cancellation has been occurring at other universities – politics and government policy, societal issues, DEI – are not intrinsic to most of the STEM disciplines.

Some of the survey data presented at the Censorship of the Sciences Conference, including FIRE’s first survey of faculty at four-year colleges (Honeycutt, 2024), also focused on political or ideological segmentation as a presumed primary cause or strong contributing factor to censorship of faculty members. This explanation notes that most university faculty members are on one side of these spectrums. The presumption is that most incidents of faculty censorship are by faculty from the dominant political or ideological affiliation censoring faculty from the minority affiliation or who do not profess dominant views. The polling data at MIT did not explore this potential cause of self-censorship, but anecdotal evidence suggests that this is not a major consideration in causing self-censorship among MIT faculty.

The polling data among MIT faculty indicates continuing self-censorship among a meaningful number of the faculty. The data are relatively consistent despite different polling methodologies used in the three polls over four years. Only the FIRE survey was designed as a representative survey across the entire faculty and is publicly available. The 2021 and 2024 polls were not published publicly but were provided by faculty members. The participants in these polls selected themselves to participate in a meeting or poll on this issue. With these considerations, this sequence of polling results cannot be interpreted as statistically representative across the entire faculty, but the participation rates are sufficient to indicate that a self-censorship problem exists.

The polling data make clear that MIT faculty perceive that senior administration and academic leadership play a role in suppressing speech at MIT. MIT faculty self-censor in response to that perception. Even when censorship and cancellation is not performed by the senior leadership themselves, cancellation can only occur if it is enabled by the leadership, whether by active measures or by fostering the perception among the faculty that the leadership does not oppose suppression of unpopular viewpoints. Student complaints alone cannot affect a faculty member, but only if the student complaints about faculty speech are given legitimacy and acted on by the administration. Administration action against its faculty over complaints about lawful and policy-compliant speech or actions – such as expressing personal viewpoints or upholding grading standards – infringe on the academic freedom of the faculty. It is ultimately the university leadership that determines whether cancel culture dominates that university, not students or a subset of faculty extremists.

4. Hope at MIT

At a STEM-focused institution like MIT, the faculty are grounded in the values of rational thinking, empiricism, and the scientific method. Historically, people at MIT have engaged in spirited, civil open discourse, tolerated different and even quirky viewpoints, and embraced the freedom of faculty and researchers to pursue their individual directions. Before 2022, MIT never had a formal policy supporting free speech and academic freedom because it had never been necessary to state the obvious. In this STEM-centric milieu, the faculty are not the source of cancel culture but rather are its antidote. Despite widespread self-censorship out of fear of cancel culture retaliation, the faculty at MIT are slowly responding to restore the Institute’s traditional values and practices.

A prime example is the faculty rebelled over the Abbot Cancellation, discussed above, whereby a significant number of the MIT faculty publicly signed an open letter letter calling for MIT to adopt a formal policy supporting free speech modeled after the Chicago Principles (MIT Faculty, 2021).

The MIT faculty were then charged by the Institute leadership to create an ad hoc committee to consider what type of formal free speech policy MIT should have (MIT, 2022a). Through 2022, this ad hoc committee developed a proposed policy on freedom of expression and academic freedom modeled after the Chicago Principles but tailored for MIT. This proposed policy was then debated and modified in forums open to the entire faculty. The culmination of this effort was MIT’s Statement on Freedom of Expression and Academic Freedom, which was adopted in a general faculty meeting in December, 2022 (MIT, 2022b). Two months later, the newly installed president of MIT endorsed this Statement as Institute-wide policy (MIT, 2023b).

The MIT faculty ad hoc committee had not just defined a policy statement, but they also made ten specific recommendations on how MIT could implement the policy. In late 2023, MIT’s president established another faculty committee to propose implementation plans for those recommendations and to consider other changes to support free speech. The MIT administration also relied on advice from this committee, the Committee on Academic Freedom and Campus Expression (CAFCE), to help it navigate through many of the free expression issues arising on campus from the conflict in Gaza (MIT, 2024a). This faculty-led committee has supported the rights of students and faculty to express themselves over the conflict while maintaining MIT’s appropriate restrictions on the time, place, and manner of expression. MIT’s restrictions, consistent with the Chicago Principles, are intended to avoid disruption of the essential activities of the Institute. The faculty committee continues work on implementing MIT’s Statement on Freedom of Expression and the recommendations that were made with it.

As mentioned earlier, in the spring of 2024, MIT became the first elite private university to ban the use of DEI statements for faculty hiring and promotion after having previously required them (MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2024). This ban was made by the senior administration and academic leadership after a poll of the MIT faculty indicated that they were generally loathed and considered dysfunctional. Following MIT’s example, several other private and public universities made similar commitments to forbid the use of DEI statements in faculty hiring (Confessore & Freiss, 2024; Robinson & Shah, 2024).

In October 2024, a group of MIT faculty founded the MIT Council on Academic Freedom (MITCAF) (MIT, 2024b). The formation of this independent group is intended to defend the values espoused in MIT’s Statement on Freedom of Expression. It is modeled after other independent faculty council groups established at other universities, particularly the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard. This council is another sign of the MIT faculty’s increasing assertiveness and confidence in defending freedom of expression at MIT.

The Abbot Cancellation was a wake-up call for many members of the MIT community, especially faculty and alumni, that the prevailing national culture and minority illiberal elements inside MIT had been successfully eroding MIT’s traditional commitment to free expression, civil discourse, intellectual diversity, and academic freedom. That gradual erosion had built a climate of fear among the faculty that led many of them to practice self-censorship. Since that seminal event, the MIT faculty have engaged in an incremental process to recommit to those values. The faculty are courageously pursuing this objective despite uncertain support from the senior administration and the academic leadership.

Recent polling data indicates that self-censorship is a problem among STEM faculty at the leading STEM university in the US. Comparable surveys suggest that self-censorship likely exists in STEM departments at other universities as well. The MIT faculty is now engaged to restore a culture that encourages open discourse and viewpoint diversity. MIT’s success in this endeavor can serve as a model for other universities to emulate.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

References

- Confessore, N.; Freiss, S. University of Michigan ends required diversity statements. The New York Times. 5 December 2024. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Frey, K.; Stevens, S. Scholars under fire: Attempts to sanction scholars from 2000 to 2022; The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, 2023; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Frey, K.; Stevens, S. T.; Lan, A.; Goldstein, A. FIRE report: MIT’s institutional health; Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, 2023; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Hinkel, L. PAOC faculty fact-check MIT Colleague on climate science. Climate@MIT. 2017. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Honeycutt, N. Silence in the classroom: The 2024 FIRE Faculty Survey Report; The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, 2024; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Ad hoc working group on free expression; IT Faculty Governance, 2022a; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. 2022 update on the free expression statement; MIT Faculty Governance, 23 December 2022b; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Report of the treasurer for the year ended June 30, 2023; MIT Office of the Vice President for Finance, 30 June 2023a; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Letter to the MIT community: Embracing freedom of expression in the life of the Institute. MIT News. 17 February 2023b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Ad hoc committee on academic freedom and campus expression. 2024a. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. MIT council on academic freedom; MIT Council on Academic Freedom, 2024b; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Faculty & instructional staff; MIT Facts, 21 August 2025a; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT. Statistics & Reports: Undergraduate majors count; MIT Registrar’s Office, 21 August 2025b; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT Faculty. The Chicago Principles (adapted for MIT). freespeech@mit. 2021. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT Free Speech Alliance. Father Maloney’s removal; MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022a; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT Free Speech Alliance. The abbot cancellation; MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022b; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT Free Speech Alliance. Four reasons MIT alumni are still angry about the Abbot Cancellation; MIT Free Speech Alliance, 2022c; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- MIT Free Speech Alliance. MIT ends use of DEI statements; MIT Free Speech Alliance, 22 May 2024; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Quacquarelli Symonds. QS World University Rankings: Top global universities; QS Top Universites, 21 August 2025; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Robinson, T.; Shah, N. Harvard faculty of arts and sciences will no longer require diversity statements; The Harvard Crimson, 4 June 2024; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Times Higher Education. World university rankings 2025; Times Higher Education, 2025; Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- U.S. News; World Report. 2025 Best graduate engineering schools. U.S. News & World Report: Education. 21 August 2025a. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- U.S. News; World Report. U.S. news best colleges. U.S. News & World Report: Education. 21 August 2025b. Available online: link to the article (accessed on 2 October 2025).

| 1 | A set of principles created by the University of Chicago in 2014, highlighting a commitment to freedom of speech and freedom of expression on US college campuses. |

| 2 | FIRE sent the survey to all 1090 MIT faculty members, and to a subset of 385 additional post-doctoral researchers and graduate students, for a total survey population of 1475. The 195 individuals who completed the survey indicate a response rate of 13%. This contrasts favorably with an overall 5.57% response rate in FIRE’s general 2024 faculty survey, in which 6,269 faculty members responded from among 112,510 total faculty members at 55 universities. FIRE references a study which indicates that “surveys with response rates ranging from 5%–54% indicate that studies with a lower response rate are only marginally less accurate than those with higher response rates,” indicating that results from both surveys are statistically valid and comparable. |

| 3 | Tables may not add to 100% because FIRE did not show “No Response” in their results. |

| 4 | Results of the Pulse of the Faculty polls are not released publicly; a copy of the results of this poll question from April 2024 was provided to the author. |

© 2025 Copyright by the author. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).